“Ma lo capisci che ogni pedalata che dai a quella benedetta macchina è una mazzata che diamo ai fascisti e ai tedeschi??!!”

Da un po’ di tempo non scrivo sul blog, avevo bisogno di uno spiraglio creativo lungo questo annus horribilis di pandemia che ci sta rendendo ancor più vulnerabili, mettendo a nudo la radicale fragilità di un sistema al collasso da tempo.

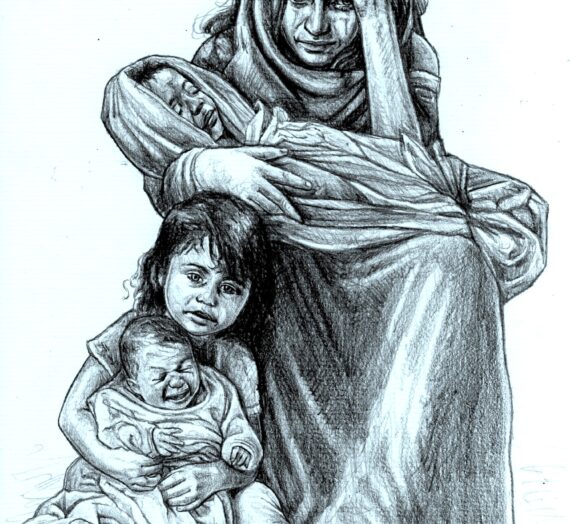

Non siamo diventati “migliori”, anzi, ci siamo incattiviti, illudendoci di superare – senza rinunciare a nulla – un’obsolescenza che ci pervade a livello intimo. Abbiamo memoria breve, in fondo, e tanta sacrosanta paura, interconnessi ma incredibilmente soli. Nel frattempo i disastri climatici e ambientali diventano irrecuperabili, i conflitti vengono giustificati mentre aumentano gli sfollati, siamo pietosamente soggiogati dai mercati finanziari, non sappiamo davvero a che santo votarci (tanto ci sono gli influencer, no? Lasciamo perdere).

Libertà, verità, presa di coscienza, rischiano di risuonare a vuoto per noi sordi. Arte, cultura, educazione, condivisione servono ancora? Mi piace pensare che aiutino a reagire, capire, immedesimarsi, ritrovare valori. Che diventino necessari, se efficaci.

Per questo vi racconto di un progetto che parla di libertà e reclusione, di paura e speranza. In pratica l’unico vero intervento di peso che sia riuscita a realizzare quest’anno poiché purtroppo, come la maggior parte degli artisti, ho visto cancellare o rimandare (ma a quando?) praticamente tutti i lavori che avevo in programma per il 2020. Tutti.

A febbraio mi contatta Sebastiano Matarazzo (aka Seba MAT), dell’Ass. TotArt, con l’intento di coinvolgermi in un progetto di Arte Urbana all’interno del Parco della Memoria di Correggio (RE), in collaborazione con l’A.N.P.I. locale e il Comune.

Gli dico che normalmente non accetto commissioni, esigo il soggetto libero per meglio esprimermi senza vincoli (bla, bla, bla, chi mi conosce sa quanto sono pesante) eppure le storie che mi racconta sono talmente potenti ed evocative che alla fine non ho dubbi e decido di accettare.

Concordiamo che il pezzo sarà realizzato nel mese di aprile. Invece no, alla porta bussa l’infame Covid19 e veniamo risucchiati dalla paura. Parte il blocco totale scandito dai DPCM, 69 lunghi giorni a dimostrarci come le priorità che rincorriamo ogni giorno siano labili, che è necessario ripensare tutto, che la ‘normalità’ (ma vi piaceva davvero in fondo?) non tornerà più, altro che “andràtuttobene”.

Nasce così solo a settembre, dopo lunga gestazione e gran carico di timori, la mia doppia opera ispirata al documentario “Partigiani” (Chiesa, Ferrario, Leotti, Puccioni, Vicari 1997) e alle notizie ricavate dalle fonti dell’Archivio ANPI di Correggio (schede di Barlettai).

Clam, sulla parete più piccola dell’edificio, è il pezzo dedicato all’affascinante storia della tipografia clandestina della Resistenza, costituita nel Podere Piave a Cànolo dai fratelli Pinotti con il tipografo Gino Patroncini, un comunista che lo stato fascista aveva iscritto negli elenchi dei vigilati speciali.

Gino, che aveva lavorato in gioventù presso la tipografia dei Notari, era già stato arrestato due volte per attività sovversiva a favore del PCI e condannato alla pena detentiva. Tornato libero nel 1936, dopo aver sottoscritto a favore della Spagna repubblicana, era stato confinato a Ponza per altri due anni.

Nel 1944 Arrigo Nizzoli (che nel dopoguerra sarebbe diventato Segretario della Federazione del PCI reggiano) gli propose di coordinare il lavoro di una piccola tipografia a Correggio.

La vicenda della tipografia era iniziata nel mese di febbraio, quando Vittorio Saltini (Toti) aveva scelto il podere dei tre fratelli Pinotti come luogo per le riunioni del partito, chiedendo di potervi ospitare una macchina tipografica di undici quintali. A comporre i testi sarebbe stato Patroncini, che visse da recluso, in solaio e poi sottoterra, per 11 mesi.

I Pinotti si alternavano freneticamente alla pedalina (erano necessarie otto robuste pedalate per stampare un foglio) e i volantini furono migliaia, una quantità incalcolabile di materiali diversi (alcuni esemplari sono conservati presso il Museo Cervi di Gattatico). Monbello, il più giovane, riuscì a stamparne da solo millecinquecento, senza mai fermarsi, una fatica disumana.

Le donne poi portavano i volantini in lavanderia, li tagliavano e li confezionavano. Venivano infine consegnati in un rifugio in mezzo alla campagna, dove le staffette li recuperavano per la diffusione.

I Pinotti furono costretti a diventare schivi e inospitali e per estrema cautela allontanarono anche Nicioun, il calzolaio che diffondeva la stampa antifascista, proprio quella prodotta al podere (a sua insaputa). Gli dissero che preferivano non accettare i volantini, troppo pericoloso.

La fama dei traditori opportunisti pesò indubbiamente alla famiglia, ma salvò l’attività della tipografia alla quale contribuivano tutti con devozione (i fratelli, mamma Faustina, le due nuore, perfino i bambini), attenti ad evitare che il forte rumore della macchina svelasse il loro segreto.

In inverno, col timore di perquisizioni e rastrellamenti, la pedalina fu trasferita in un sotterraneo scavato in una sola notte sotto la stalla, proprio mentre a cento metri sfilavano truppe tedesche. Un ambiente umido, insalubre e senza aereazione (l’aria passava attraverso un tubicino) cui si accedeva in sicurezza da una botola, ma che si allagava completamente alla prima pioggia.

Patroncini lavorò in quelle condizioni fino all’uscita dell’ultimo volantino, quello che lanciava la parola d’ordine dello sciopero insurrezionale, e non fu mai scoperto, con grande sorpresa di tutti.

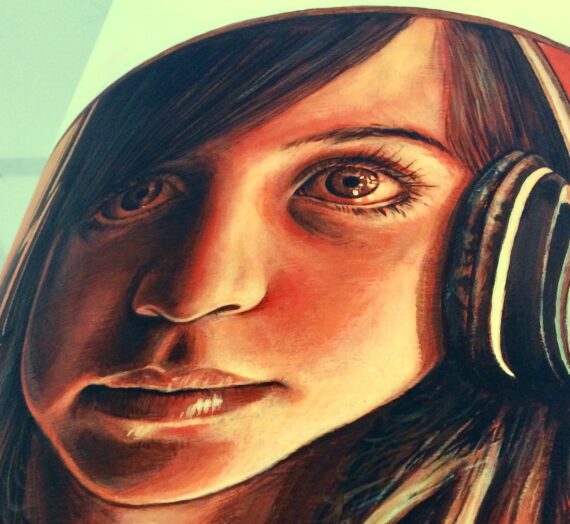

Attraverso la mia opera ho tentato di evocare l’esperienza da recluso del Patroncini, l’ambiente angusto, la luce che illumina mezzo volto provandone una sola pupilla, l’orecchio teso a percepire il pericolo esterno, l’aspetto stanco da giornate intere di attività incessante, la paura di essere scoperti. Eppure questo notturno surreale si tinge di blu ed è una luce che non proviene solo dalla candela (attorno alla quale si percepirebbe solo oscurità) ma anche dai caratteri volanti e dal personaggio stesso. Una luce irreale e magica che è la potenza della parola, della lotta attraverso le idee. Pur adottando spesso nelle mie opere la lampadina come elemento che rimanda alla coscienza, le ho preferito qui un moccolo di candela, fortemente evocativa (a Cànolo fu invece adottata una lucerna, poi sostituita da una lampadina).

Il titolo Clam vuole rimandare all’avverbio latino che significa “di nascosto, all’insaputa di” (L’etimologia della parola clandestino è da ricondursi infatti al latino clamdestinus: clam = di nascosto + dies = giorno. Colui il quale si nasconde al giorno, si occulta, si cela) ma anche allo stesso termine che in inglese vuol dire “mollusco”, richiamando l’idea del mollusco bivalve che cela al suo interno qualcosa di prezioso (e simbolico, come la verità).

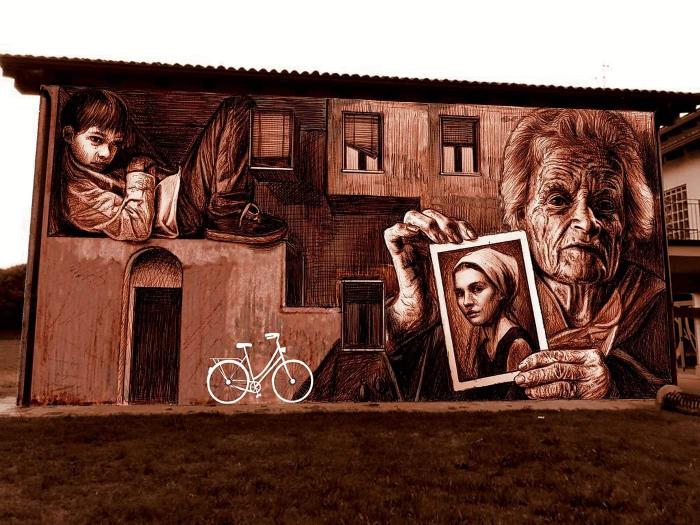

Il secondo pezzo, sulla parete grande, si intitola I campi capovolti ed è ispirato a una breve intervista, sempre tratta dal documentario del 1997, ad Iva Montermini, staffetta partigiana vissuta a Correggio.

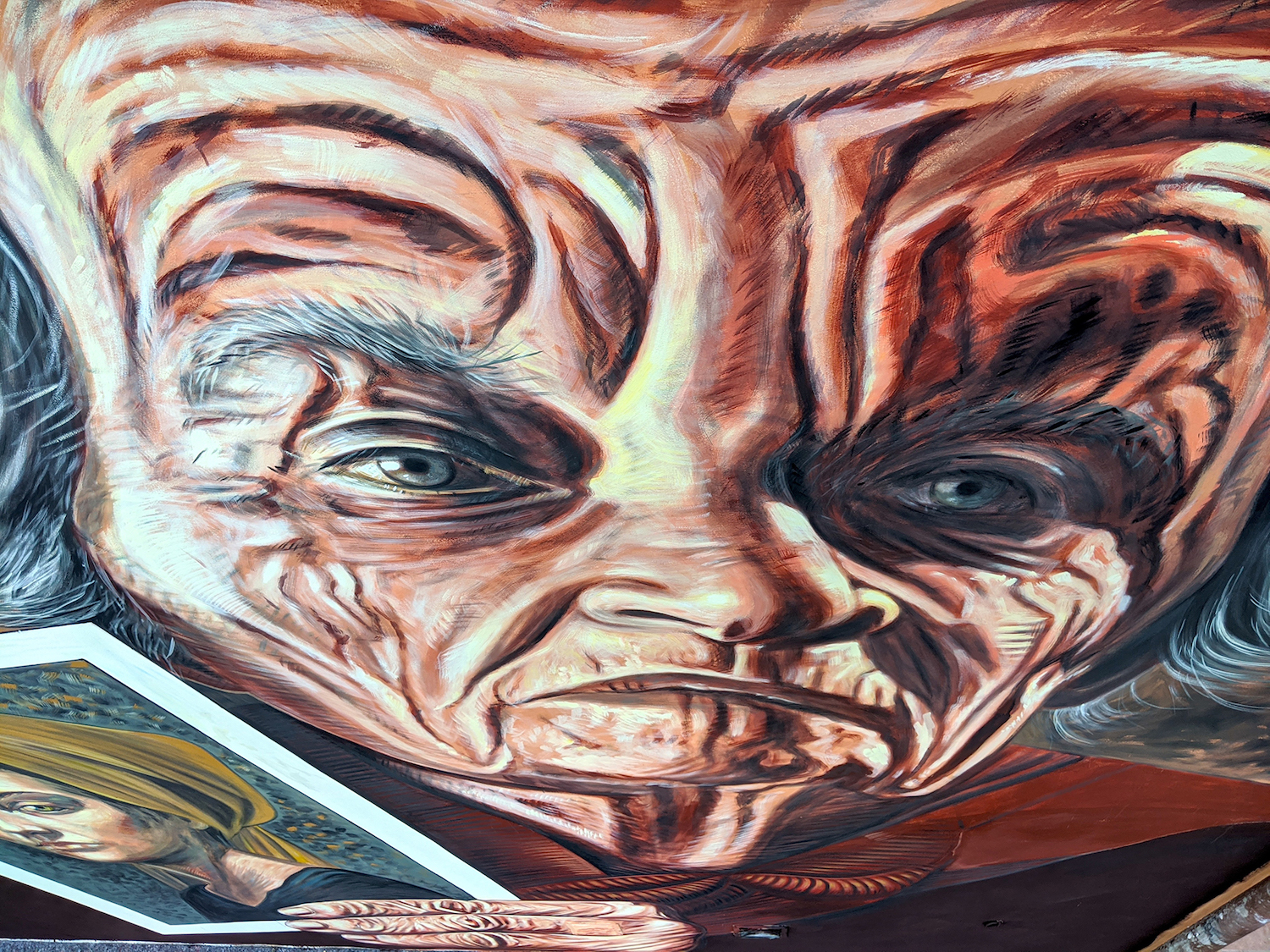

Il taglio fotografico e l’illuminazione mi impedivano di leggerne il volto in modo preciso ma ho tentato comunque di ritrarla in un omaggio. Iva, in versione monumentale, mentre accenna schiva ai tre fratelli partigiani e al fatto che una volta catturata non aveva parlato per proteggerli.

Mi hanno molto colpito le sue parole, quando ricorda che dopo una notte di interrogatorio e torture è stata liberata ed è tornata a casa attraverso i campi: “mi sembrava che il cielo fosse chissà dove” – “I campi mi parevano tutti capovolti”.

Un’epifania straziante e poetica: era talmente scombussolata dentro che anche il mondo esterno si era completamente ribaltato. Quei campi per me erano impossibili da dipingere, qualsiasi tentativo pittorico (col mio linguaggio) sarebbe stato meno potente delle sue parole.

Ma avevo lei, per occupare quel muro. Così l’ho rappresentata pensierosa, commossa, mentre mostra una fotografia di quando era giovane. In basso una silhouette di bicicletta, chiara. La bicicletta ormai non c’è più ma resta qualcosa per evocarla. Ho pensato a Platone. La sagoma luminosa non è l’ombra della bicicletta (il suo ricordo) ma l’idea stessa della bicicletta e del ruolo fondamentale che ebbe per la Resistenza.

Palpabile invece è il racconto di Iva da anziana, il ruolo prezioso della conservazione e divulgazione della ‘memoria’. Per questo motivo in alto a sinistra ho dipinto un bambino di oggi accovacciato, a rappresentare le nuove generazioni, mentre ascolta il racconto di un tempo lontano.

Durante la realizzazione dell’opera ho avuto modo di incontrare il nipote e la pronipote di Iva e alcune persone che l’avevano conosciuta, confidandomi come fosse una persona speciale. Non parlava volentieri di quel periodo della sua vita e dal documentario si percepisce l’enorme sforzo fatto per lasciar uscire almeno una parte del ricordo (a quella più amara, quella atroce, non accenna, ma non serve, si evince già). Per questo l’ho scelta. Grazie Iva.

Due opere, quindi: un interno di solaio, falsamente buio ma illuminato dalla verità, e un ritratto della memoria storica, che dalla delicatezza lascia trapelare il dramma. All’angolo fra le due il bambino in ascolto, a voler ribadire che l’educazione e la cultura restano strumenti imprescindibili per evitare il ripetersi di eventi orribili.

Era un progetto che pensavo di realizzare d’un fiato in due settimane intense (e al limite delle possibilità umane, come mio solito, accidenti a me). Invece a metà sono crollata e quindi l’intervento si è sviluppato in due momenti. Col senno di poi è stato meglio tornare, far sedimentare i contenuti e mantenere vive le emozioni, soprattutto riabbracciare (virtualmente) chi mi aveva accolto con tanto calore.

Ringrazio Seba Mat per la curatela, i fantastici soci dell’ANPI per avermi letteralmente adottata per tutto il tempo (Rina, Carmelina, Ciano, Stefania, Marco), Marzia della Biblioteca Il Piccolo Principe per la gentilezza e l’ospitalità e ovviamente il Comune di Correggio (Ilenia Malavasi e Alessandro Pelli) e il suo splendido Parco della Memoria.

Ultimo, ma primo nel cuore, Andrea Zampatti, che ringrazio per le fotografie, la dolcezza e l’infinita pazienza.