Dipinta a Covo (BG) all’interno del Festival Cure, la mia ultima opera si intitola “La mezzanotte dell’anno” ed è una reinterpretazione emotiva dell’iconografia di santa Lucia, martire siracusana vissuta alla fine del III secolo e morta sotto la persecuzione di Diocleziano.

L’idea è partita dal fatto che a Covo si trova un’antica cappella, già testimoniata dalle visite pastorali seicentesche, dove la santa compare in un affresco accanto alla Vergine di Loreto, e dalla convinzione che col pretesto di raccontarne una mia versione avrei potuto lavorare di fantasia rappresentando anche un asino (chiaramente sconosciuto all’iconografia di Lucia ma caro ai bambini bresciani e bergamaschi).

Non è una motivazione sensazionale, lo ammetto, ma da tempo avevo in mente di dipingere un asinello, creatura stupenda che adoro. Molti ricordi magici della mia infanzia infatti sono legati al 13 dicembre, la notte più corta dell’anno (ma infinita per i più piccoli).

Lucia è certamente una delle figure più care alla devozione cristiana. Credo che la maggior parte di voi conosca la sua storia, ma più nella versione popolare derivata dal culto di origine medievale. Certamente avrete visto affreschi e dipinti dove è raffigurata con gli occhi appoggiati su un piatto e per quello l’avrete immediatamente identificata. Mi avete detto tutti però che la leggenda racconta che le abbiano cavato gli occhi, eppure vi assicuro che le testimonianze storiche che riportano del suo martirio non accennano in alcun modo a questo supplizio.

Le fonti cui riferisco sono gli atti rinvenuti in due diverse redazioni: l’una in lingua greca, il cui testo più antico risale al V secolo, l’altra in quella latina, riconducibile agli inizi del VI, che di quella greca pare essere una traduzione. Se il più antico resoconto greco del martirio contiene una leggenda edificante, rielaborata da un anonimo agiografo sulla tradizione orale, ed è da alcuni ritenuto inattendibile per incongruenze varie, la Passio latina invece è stata recentemente riabilitata.

Non mi soffermerei però su questo, vorrei limitarmi a considerare entrambe le agiografie nel senso di passioni epiche, perché mi interessa per la mia opera solo una traccia che delinei una figura misteriosa ed esemplare.

Che la venerazione derivi da un preesistente culto pagano o meno non cambia a livello di suggestione ma anzi, rende più interessante la questione. Non mi addentro nella storia intrigante e complessa della duplice traslazione delle reliquie – da Siracusa a Costantinopoli, dalla Germania fino a Venezia – e delle peripezie durate quasi novecento anni perché questo post diventerebbe insostenibile (avete paura, eh?).

Si legge che Lucia si consacrò segretamente a Dio con voto di perpetua verginità, ma venne promessa in sposa a un pretendente. Dopo un pellegrinaggio alla tomba di sant’Agata a Catania, con la madre Eutichia gravemente malata, Lucia vide in sogno Agata, la quale le confermò la guarigione della madre indicandone Lucia stessa ad intercessione e predicendo il suo futuro martirio. Lucia allora confessò ad Eutichia di voler rinunciare al matrimonio ed elargire tutte le proprie ricchezze ai poveri.

La Passio riporta che da ricca si fece povera, e per circa tre anni si dedicò senza interruzione alle opere di misericordia a vantaggio dei poveri, degli orfani, delle vedove e degli infermi. Ma colui che l’aveva pretesa come sposa si vendicò del rifiuto denunciandola al locale tribunale dell’impero romano, con l’accusa che ella fosse “cristianissima”. Arrestata, venne processata dal governatore Pascasio. Ella rispose senza timore, quasi esclusivamente citando la sacra scrittura e, rimasta miracolosamente illesa da crudeli torture, profetizzò l’imminente fine delle persecuzioni di Diocleziano.

Quando Pascasio tentò di infliggerle la pena del postribolo, la vergine divenne inamovibile tanto che nessun tentativo di trasportarla riuscì, allora si ordinò che fosse bruciata ma neanche il fuoco poté scalfirla. Infine morì con un colpo di spada in gola. Era il 13 dicembre dell’anno 304 (vi sono studiosi che propendono per altre datazioni: 303, 307 e 310. Sorvolo invece sul Martirologio Geronimiano e sui vari testi liturgici bizantini e occidentali, che propongono datazioni diverse dal 13 dicembre).

Se gli atti non parlano quindi di un martirio degli occhi, probabilmente il collegamento con la vista fu dato dall’etimologia latina del nome – Lux = luminosa, splendente – molto diffusa soprattutto in testi agiografici bizantini e del Medioevo Occidentale. L’iconografia, già a partire dal Trecento, divulgò questa leggenda raffigurando la santa con il simbolo connotativo degli occhi su un piatto o su un vassoio, unitamente alla palma, alla lampada e, con meno frequenza, anche con altri elementi del suo martirio, il libro, il calice, la spada, il pugnale o le fiamme.

Quindi in sostanza dal Medioevo in poi si consolidò sempre più la taumaturgia di Lucia quale patrona della vista. Inoltre, nella Legenda Aurea di Iacopo da Varazze, opera imprescindibile per le scelte iconografiche legate alle agiografie, il testo dedicato a Lucia è preceduto da un preambolo sulle varie valenze etimologiche e simboliche dell’accostamento Lucia/luce.

Alla luce accenna anche il Martirologio Romano nella Memoria di santa Lucia “che custodì, finché visse, la lampada accesa per andare incontro allo Sposo e, a Siracusa in Sicilia condotta alla morte per Cristo, meritò di accedere con lui alle nozze del cielo e di possedere la luce che non conosce tramonto”.

Ma arriviamo alla mia opera.

Il titolo è ispirato al verso di un’opera di John Donne, poeta metafisico inglese dei Seicento: Notturno sopra il giorno di Santa Lucia, il più breve dell’anno. L’ho recentemente ritrovato in un saggio intenso di Cristina Campo (La Tigre Assenza) e mi ha colpita. Il giorno di santa Lucia è definito “la mezzanotte dell’anno” (“the years midnight”) perché è il più breve. A quanto pare non è vero, il giorno più corto sarebbe il 21 dicembre, ma qualche certezza in questo post la dobbiamo pure avere e adesso ignoriamo la precisazione! Il giorno di Lucia per sole sette ore solleva la sua maschera.

La composizione fu scritta, probabilmente, nel dicembre del 1611. Il poeta, che si era allontanato dolorosamente dalla moglie incinta per un viaggio a Parigi, ebbe, in sogno, una visione terribile di lei, con un bambino morto fra le braccia. Spaventato, spedì un corriere a Londra per sincerarsi delle sue condizioni.

E fu nella tremenda attesa che nacquero le cinque stanze del Nocturnal, dove la desolazione della terra spoglia è festosa se confrontata allo stato d’animo del poeta, che dice “sono niente, sono nulla, sono annichilito” e anche “Tutto è a me superiore (…) persino l’ombra, per esser tale, deve vantare un qualcosa che la produca, un corpo e la luce”.

In coda trovate il notturno completo, in italiano e inglese. Sono rimasta turbata dalla poesia (è incredibile quanto tutto ci paia autobiografico a volte) e pur citando il poeta nel titolo ho voluto per reazione coprire il capo della mia Lucia di fiori, frutti, foglie, insetti palpitanti, colore. Una versione rigogliosa che esaltasse la caparbietà emersa dalla Passio ma lasciasse lo sguardo fuggevole della martire impresso nei passanti. Un volto che potesse anche ispirare soggezione, mentre il muso dolce dell’asino faceva capolino perdendo la mansuetudine del bozzetto per assumere un atteggiamento più teso. Il dettaglio degli occhi come attributo iconografico è presente ma in una visione più soft che è quella di una piantina le cui foglie “ci osservano” e che culmina in un giglio, simbolo di candore. La suggestione è nata osservando la santa Lucia di Francesco del Cossa conservata a Washington, la quale regge gli occhi su una sorta di piantina. E’ un’opera stupenda.

Alla fine, seppur il mio intento fosse quello di dipingere l’asino e trasferire lì la forza dell’opera, mi sono resa conto di aver messo la potenza in Lucia, con un’intensità che la rende interiormente inamovibile ma ne lascia trapelare i timori. Ne è uscito un notturno interiore (mio, della martire, del poeta) che emana luce, una sorta di paradosso cromatico, colore che nasce dall’ombra come primavera che esplode nell’inverno.

Permane però un’inquietudine, l’ombra incancellabile di una morte violenta che mi ha ricordato le molte altre precedenti o coeve e soprattutto una di poco posteriore che ho amato alla follia, Ipazia di Alessandria, illustre vittima del fanatismo di quegli stessi cristiani che fino a cent’anni prima erano perseguitati.

Fosse relegata al passato questa sofferenza, forse potremmo edulcorarla. Invece mi ha fatto pensare alle molte vittime di ogni giorno, le vite tolte in nome di un egoismo che qualcuno chiama atrocemente amore ma che è soltanto possesso, un’altra forma di fanatismo.

Vi lascio con un’indicazione tecnica, per alleggerire.

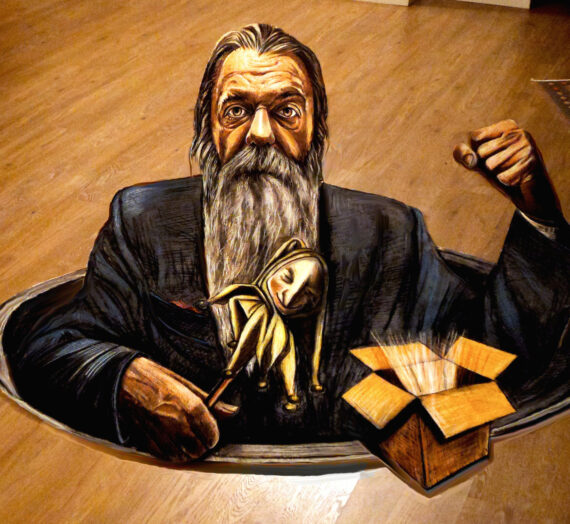

L’opera è anamorfica e va vista arrivando da destra. Vi accorgerete camminando che il dipinto si distorce fino ad essere allargato e schiacciato dal lato opposto al punto di vista. Fotografatelo da davanti e poi di lato oppure provate a registrare un piccolo video camminando e lo vedrete riformarsi.

Fateci un reel, che a me tremano le mani, per vari motivi.

Grazie per aver letto fino in fondo!

Per i temerari: leggete della traslazione delle reliquie di santa Lucia, prendete le vicende come volete ma apprezzatene la densità da sogno.

Grazie ad Alberto Gatti, alla Proloco e al Comune di Covo, a Roberto per la cornice perfetta, alle famiglie di Laura e Aurelio che hanno accolto l’opera, a chi è passato a trovarmi, alla prof. di Lettere che ha portato i ragazzi delle medie e conoscermi, ad Antonella, all’Osteria del crostino, Maccalli e ai tre custodi quotidiani che hanno accompagnato l’opera: Domenico, Mario e Lino.

Le fotografie sono di Andrea Zampatti.

——–

John Donne – Notturno sopra il giorno di Santa Lucia, il più breve dell’anno

——–

Questa è la mezzanotte dell’anno e lo è del giorno

di Lucia, che per sole sette ore

solleva la sua maschera.

Il sole è esausto e ora le sue fiasche

spremono tenui sprazzi, nessun raggio costante.

Tutta la linfa del mondo è caduta.

L’universale balsamo bevve la terra idropica;

là, quasi a piè del letto, s’è ritratta la vita

morta e interrata. Eppure tutto ciò sembra ridere

appetto a me che sono il suo epitaffio.

Dunque studiatemi, voi che sarete amanti

in altro mondo, un’altra primavera:

sono ogni cosa morta onde operò l’amore

nuova alchimia. Perché una quintessenza

distillò la sua arte anche dal nulla,

da opache privazioni e da scarne vuotezze.

Mi distrusse. E ora mi rigenerano

assenza, buio, morte, le cose che non sono.

Tutti gli altri da tutte le cose

traggono tutto ciò che è buono: vita, anima,

spirito, forma e ne hanno esistenza.

Io, grazie all’alambicco dell’amore,

son la fossa di tutto ciò che è nulla.

Spesso noi due piangemmo

un diluvio e ne fu sommerso il mondo:

noi due. E tramutammo spesso

fino a due caos quando mostrammo cura

d’altri che noi, e talora l’assenza,

rubandoci le anime, fece di noi carcasse.

Ma, grazie alla sua morte (parola che l’offende),

dal primitivo nulla io son fatto elisir;

fossi uomo, dovrei sapere d’esserlo;

preferirei, se fossi bestia, un qualche

fine od un qualche mezzo, se persino le piante,

persin le pietre detestano od amano:

tutto, tutto s’investe di qualche proprietà;

fossi un nulla qualunque, come l’ombra,

dovrebb’esservi un corpo ed una luce. Ma

sono nulla. E non vuole rinnovarsi il mio sole.

Voi, amanti, pei quali il minor sole

a quest’ora è passato in Capricorno

per succhiarne voluttà nuova e donarla a voi,

o voi tutti, godetevi l’estate.

Poiché ella gode la sua lunga festa

notturna, lasciate ch’io m’accinga

verso di lei, lasciate che io chiami quest’ora

la sua Vigilia, la sua Veglia. Questa

è mezzanotte fonda, e dell’anno e del giorno

(And now in English)

Painted in Covo (BG) within CURVE Festival, my latest work is entitled “Midnight of the year” and is an emotional reinterpretation of the iconography of Saint Lucia, a Syracusan martyr who lived at the end of the 3rd century and died under the persecution of Diocleziano.

The idea started from the fact that in the town there is an ancient chapel, already witnessed by the seventeenth-century pastoral visits, where the saint appears in a fresco next to the Virgin of Loreto, and from the conviction that under the pretext of telling my version I could working with imagination also representing a donkey (clearly unknown to Lucia’s iconography but dear to the children of Brescia and Bergamo, where the saint brings gift to children thanks to a donkey).

It’s not a sensational motivation, I admit it, but I’ve had in mind for some time to paint a donkey, a wonderful creature that I adore. In fact, many magical memories of my childhood are linked to December 13, the shortest night of the year (but infinite for the little ones).

Lucia is certainly one of the figures dearest to Christian devotion. I believe most of you know the story of her but more in the popular version derived from the medieval origin cult. You will certainly have seen frescoes and paintings where she is depicted with her eyes resting on a plate and you will have immediately identified her. You have all told me, however, that the legend of her tells that her eyes were gouged out, yet I assure you that the historical testimonies that report her martyrdom do not in any way mention this torture.

The sources to which I refer are the documents found in two different editions: one in Greek, whose oldest text dates back to the fifth century, the other in Latin, attributable to the beginning of the sixth century, which appears to be a translation. If the oldest Greek account of martyrdom contains an edifying legend, reworked by an anonymous hagiographer on the oral tradition, and is considered by some to be unreliable due to various inconsistencies, the Latin Passio instead has recently been rehabilitated. However, I would not dwell on this, I would like to limit myself to considering both hagiographies in the sense of epic passions, because for my work I am only interested in a trace that outlines a mysterious and exemplary figure.

Whether the veneration derives from a pre-existing pagan cult or not does not change at the level of suggestion but rather makes the question more interesting. I won’t go into the intriguing and complex story of the double translation of the relics – from Syracuse to Constantinople, from Germany to Venice – and the vicissitudes that lasted almost nine hundred years because this post would become unsustainable.

We read that Lucia secretly consecrated herself to God with a vow of perpetual virginity, but she was promised in marriage to a suitor. After a pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint Agatha in Catania, with her mother Eutichia gravely ill, Lucia saw Agata in a dream, who confirmed her mother’s healing, indicating Lucia herself as an intercession and predicting her future martyrdom. Lucia then confessed to Eutichia that she wanted to renounce the marriage and give all her wealth to the poor.

The Passio reports that from being rich she became poor, and for about three years she dedicated herself without interruption to works of mercy for the benefit of the poor, orphans, widows and the infirm. But the one who had demanded her as her wife, took revenge for her refusal by denouncing her to the local court of the Roman Empire, with the accusation that she was “very Christian”. She was arrested, she was tried by Governor Pascasio. She answered fearlessly, almost exclusively quoting sacred scripture and, miraculously unharmed by cruel tortures, she prophesied the imminent end of Diocleziano’s persecutions.

When Pascasio tried to inflict the brothel penalty on her, her virgin became immovable so much that no attempt to transport her succeeded, so she was ordered to be burned but not even her fire could scratch her. She finally died with a sword blow in the throat. It was December 13 of the year 304 (there are scholars who favor other datings: 303, 307 and 310. I overlook the Geronimian Martyrology and the various Byzantine and Western liturgical texts, which propose different dates from December 13).

Therefore, if the documents do not speak of a martyrdom of the eyes, the connection with sight was probably given by the Latin etymology of the name – Lux = bright, shining – very widespread especially in Byzantine hagiographic texts and those of the Western Middle Ages. The iconography, already starting from the fourteenth century, popularized this legend by depicting the saint with the connotative symbol of the eyes on a plate or tray, together with the palm, the lamp and, less frequently, also with other elements of her martyrdom, the book, the goblet, the sword, the dagger or the flames.

Well, essentially from the Middle Ages onwards, Lucia’s thaumaturgy as patroness of sight was increasingly consolidated. Also in the Golden Legend by Iacopo da Varazze, an essential work for the iconographic choices, the text dedicated to Lucia is preceded by a preamble on the various etymological and symbolic values of the combination Lucia/light.

The Roman Martyrology also mentions the light in the Memory of Saint Lucia “who kept, as long as she lived, the lighted lamp to go to meet the Bridegroom and, in Syracuse in Sicily led to death for Christ, deserved to enter with him at the heavenly wedding and to possess the light that knows no setting”.

But let’s get to my work. The title is inspired by the verse of a work by John Donne, an English metaphysical poet of the seventeenth century: Notturno sopra il giorno di Santa Lucia, the shortest day of the year. I recently found it again in an intense essay by Cristina Campo (La Tigre Assenza) and it struck me. Saint Lucia’s day is called “the years midnight” because it is the shortest. Apparently it is not true, the shortest day would be December 21st, but we must also have some certainty in this post and now we ignore the clarification! Lucia’s day for only seven hours lifts her mask.

The composition was probably written in December 1611. The poet, who had painfully left his pregnant wife for a trip to Paris, had a terrible dream in a dream: of her, with a dead child in her arms. Frightened, he sent a courier to London to make sure of his condition.

And it was in the tremendous expectation that the five rooms of the Nocturnal were born, where the desolation of the bare earth is festive when compared to the mood of the poet, who says “I am nothing, I am nothing, I am annihilated” and also “Everything is up to me superior (…) even the shadow, to be such, must boast something that produces it, a body and light”. At the end you will find the complete nocturne.

I was disturbed by the poem (it’s incredible how autobiographical everything seems to us at times) and while quoting the poet in the title, I wanted to cover my Lucia’s head with flowers, fruits, leaves, palpitating insects, color as a reaction. A luxuriant version that exalted the stubbornness that emerged from the Passio and left the martyr’s fleeting gaze imprinted on passers-by. A face that could also inspire awe, while the sweet muzzle of the donkey peeped out, losing the meekness of the sketch to assume a more restless attitude. The detail of the eyes as an iconographic attribute is present but in a softer vision which is that of a plant whose leaves “observe us” and which culminates in a lily, a symbol of innocence. The suggestion was born by observing the saint Lucia by Francesco del Cossa preserved in Washington, which holds its eyes on a sort of map. It’s a wonderful work.

In the end, although my intent was to paint the donkey and transfer the strength of the work there, I realized that I had put power in Lucia, an intensity that makes her internally immovable but lets her fears leak out. The result is an inner nocturnal (mine, the martyr’s, the poet’s) that emanates light, a sort of chromatic paradox, a color that arises from the shadows like spring exploding in winter.

However, a disquiet remains, the indelible shadow of a violent death which reminded me of the many other previous or contemporary ones and above all a slightly later one which I madly loved, Ipazia from Alexandria, illustrious victim of the fanaticism of those same Christians who until a hundred years earlier they were victims.

If this suffering were relegated to the past, perhaps we could sweeten it. Instead it made me think of the many victims of every day, the lives taken in the name of a selfishness that someone atrociously calls love but which is only possession, another form of fanaticism.

I’ll leave you with a technical indication, to lighten things up. The work is anamorphic and must be seen coming from the right. You will notice as you walk that the painting distorts until it is enlarged and crushed on the side opposite to the point of view. Take a little video walking and you’ll see him reform.

Make us a reel, my hands are shaking.

Thanks for reading this far!

For the daredevils: read about the translation of the relics of Saint Lucia, take the story as you like but appreciate its dreamlike density.

———–

John Donne – A Nocturnal upon St. Lucie’s day, being the shortest day

A Nocturnal upon St. Lucie’s day, being the shortest day

TIS the year’s midnight, and it is the day’s,

Lucy’s, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks;

The sun is spent, and now his flasks

Send forth light squibs, no constant rays;

The world’s whole sap is sunk;

The general balm th’ hydroptic earth hath drunk,

Whither, as to the bed’s-feet, life is shrunk,

Dead and interr’d; yet all these seem to laugh,

Compared with me, who am their epitaph.

Study me then, you who shall lovers be

At the next world, that is, at the next spring;

For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

For his art did express

A quintessence even from nothingness,

From dull privations, and lean emptiness;

He ruin’d me, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death—things which are not.

All others, from all things, draw all that’s good,

Life, soul, form, spirit, whence they being have;

I, by Love’s limbec, am the grave

Of all, that’s nothing. Oft a flood

Have we two wept, and so

Drown’d the whole world, us two; oft did we grow,

To be two chaoses, when we did show

Care to aught else; and often absences

Withdrew our souls, and made us carcasses.

But I am by her death—which word wrongs her—

Of the first nothing the elixir grown;

Were I a man, that I were one

I needs must know; I should prefer,

If I were any beast,

Some ends, some means ; yea plants, yea stones detest,

And love; all, all some properties invest.

If I an ordinary nothing were,

As shadow, a light, and body must be here.

But I am none; nor will my sun renew.

You lovers, for whose sake the lesser sun

At this time to the Goat is run

To fetch new lust, and give it you,

Enjoy your summer all,

Since she enjoys her long night’s festival.

Let me prepare towards her, and let me call

This hour her vigil, and her eve, since this

Both the year’s and the day’s deep midnight is.